It had to happen, we can’t put it off any longer. We need to talk about what commissioning is. Or is not.

It could be presented in a plain, factual manner … there are stages to commissioning, these are arranged in a cyclical process.

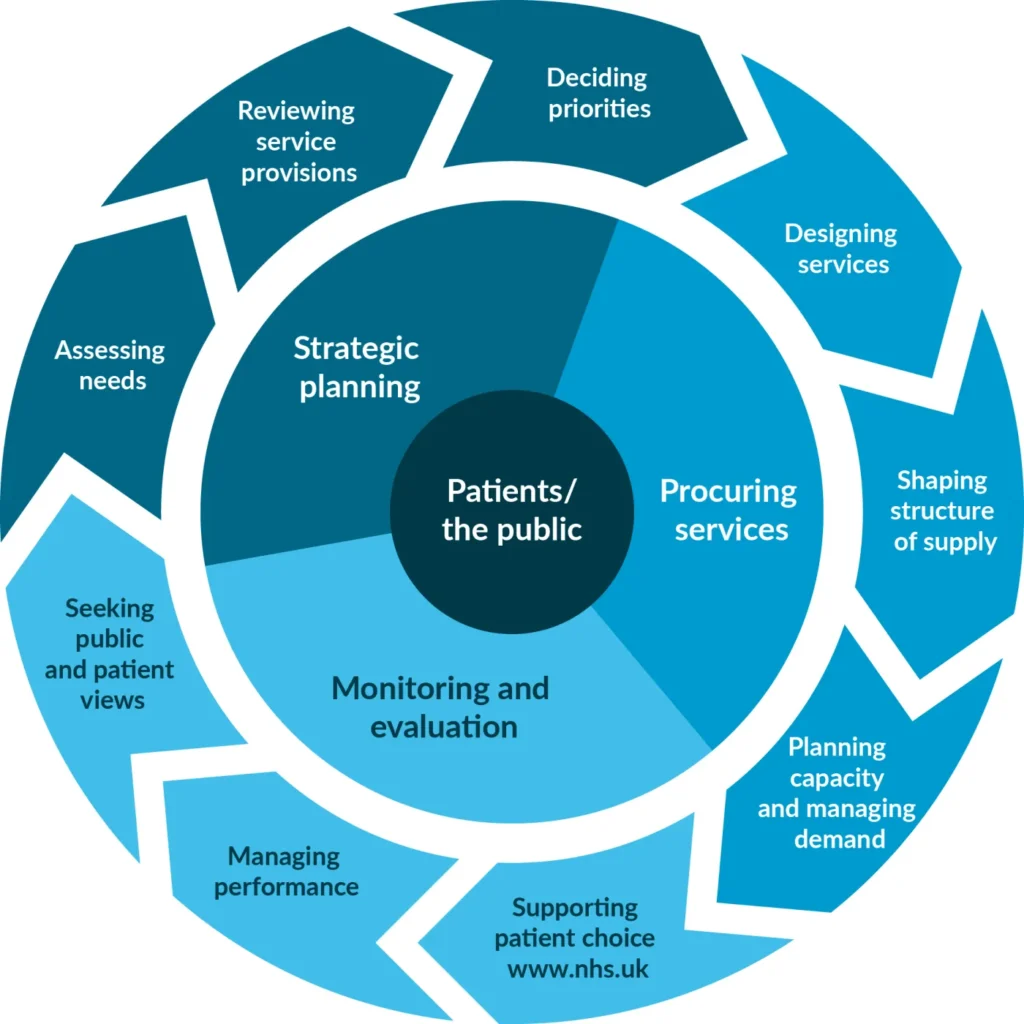

Here’s the obligatory diagram describing the key stages of commissioning – its from the NHS, they love a process:

Most explanations start you with ‘Assessing needs’, proceeding through to designing and planning.There’s a tricky bit after, referred to as ‘shaping the market’ or ‘market making’ (like a crafts workshop). This is essentially the point where it becomes clear that no-one is providing the service you need – more likely there are plenty of providers, but none of them do quite the job. So a commissioner has to consider how they ’shape’ provision to meet their beautifully designed service specification. Skipping through that bit means we arrive at ‘Procurement’. This might feel like firmer ground – there are often teams of people skilled in procurement, contracts, the law. With larger procurements, a commissioner might find themselves handing it all over to procurement teams – and in some instances it can feel as if its disappeared into a different world and language. Eventually (usually very eventually) a contract emerges with a provider attached. There can even be a brief period of elation, or perhaps its relief, as the new service provider sets up, announces its existence. This may occasionally be marred by the need to quietly, if possible, manage the old provider, or those providers who didn’t get the contract and who think they could still do a better job. It’s all very energy consuming.

Then, as a colleague once said to me, ‘now it’s simple, they do their job, we performance manage them’. Until the contract approaches its end date. Or, more usually, the service being provided doesn’t meet the needs of those using it – or those who need it but don’t use it. This is also a tricky bit – who is to blame? The provider for being inefficient in the face of people with individual needs? The commissioner for not getting the service specification right? Or the funding for not meeting the actual costs? Or – and yes, this does get used – the people who use the service for not understanding how to use it?

The issue I have with the ‘commissioning cycle’ is that it is often applied as if it’s an instruction manual – follow these steps and proceed to the end. In my various roles as a public sector ‘commissioner’, there has usually been some form of assurance or performance framework applied to these acts of commissioning by a regulatory body. These frameworks usually worked from this commissioning cycle, setting standards for each stage and requiring us jobbing ‘commissioners’ to present evidence that we are meeting these standards at each stage. Before this becomes too much like whingeing (as if), it is understandable, this approach to assurance – how do you learn what works if you don’t look for evidence? (My research and academic colleagues will be rushing to engage that debate …). The problem with the approach is it assumes commissioning is procedural, that it is largely about understanding the stage you are in and then doing the things that stage requires. Hidden within this, perhaps, is also an assumption that, well, almost anyone can do it. Give a reasonably well adapted manager (have you met any?) the commissioning manual and they’ll get through it ok. Like a recipe – the cake will come out like a cake, just take a bite and make suggestions like ‘next time perhaps use more of everything’.

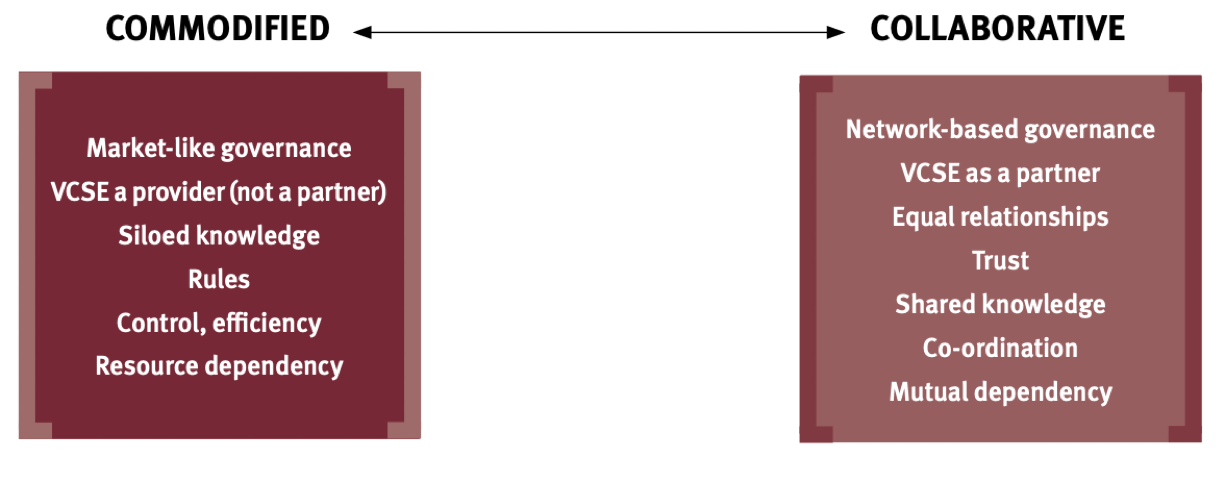

In some respects this is all true – but only if you use the commissioning cycle as a guide. There is, in my experience, a different reality of commissioning, one that has – to my knowledge, not yet been put into a neat diagram. In their report ‘Towards collaboration: VCSE and health and care commissioning relationships’ (2023), the Universities of Birmingham, Plymouth and London seem to approach something fundamental when they describe a Commodified approach to commissioning, comparing it to a Collaborative approach.

In Commodified commissioning, the stages of the commissioning cycle can be seen, glowing out beneath the surface – procedural, rules, silo-ed knowledge (and power). Yet in their description of Collaborative Commissioning, there are features that ring true with my actual experience of commissioning – shared knowledge, coordination, trust. It feels like this is pointing to some far more fundamental description of commissioning, something that stands behind all the various diagrams of commissioning cycles – as if the diagrams are the glyph we all focus on, not realising the actual goddess is there in the shadows beyond.

I once said – thinking at the time it was a facetious remark – that commissioning was not a science but an art – meaning that, in my experience, it rarely proceeded through defined stages. Instead, not unlike the best buddhism, all aspects of commissioning existed all at once, at the same time – with commissioners just a part of its reality.

A less ethereal way of seeing it is that, to commission is to understand that any aspect of the traditional commissioning stages may need to co-exist for a while and, further, there several other aspects to commissioning that might also require acknowledgement. We operate in a human world (and an increasingly stroppy environmental one) and humans, not known for their individual predictability (well, except perhaps on social media), bring all that ‘stuff’ with them – self, ego, compassion, drive, enthusiasm, pessimism, privilege, culture … and on its goes.

Instead of seeing ‘commissioning’ as a process or a cycle, it may be better to see it as a set of skills, even a vocation. And instead of seeing it as something that a small team of people – the ‘commissioners’ – ‘do’ in the world, it could be seen as a more collaborative and collegiate way of working to improve the world. Sure, that sounds idealistic, but, in my experience, real improvements rarely resulted from following the commissioning manual – they usually came from building a shared understanding – not just of what was needed but also of what could help – and of the challenge that nothing ‘off the shelf’ ever met these needs.

Leave a Reply